Taking Diagnostic to the Future with Mehdi Maghsoodnia CEO of 1Health

Today we’re talking to Mehdi Maghsoodnia, Co-founder of 1Health which is a personalized precision medicine powered by a lab testing platform that connects labs, clinicians and consumers.

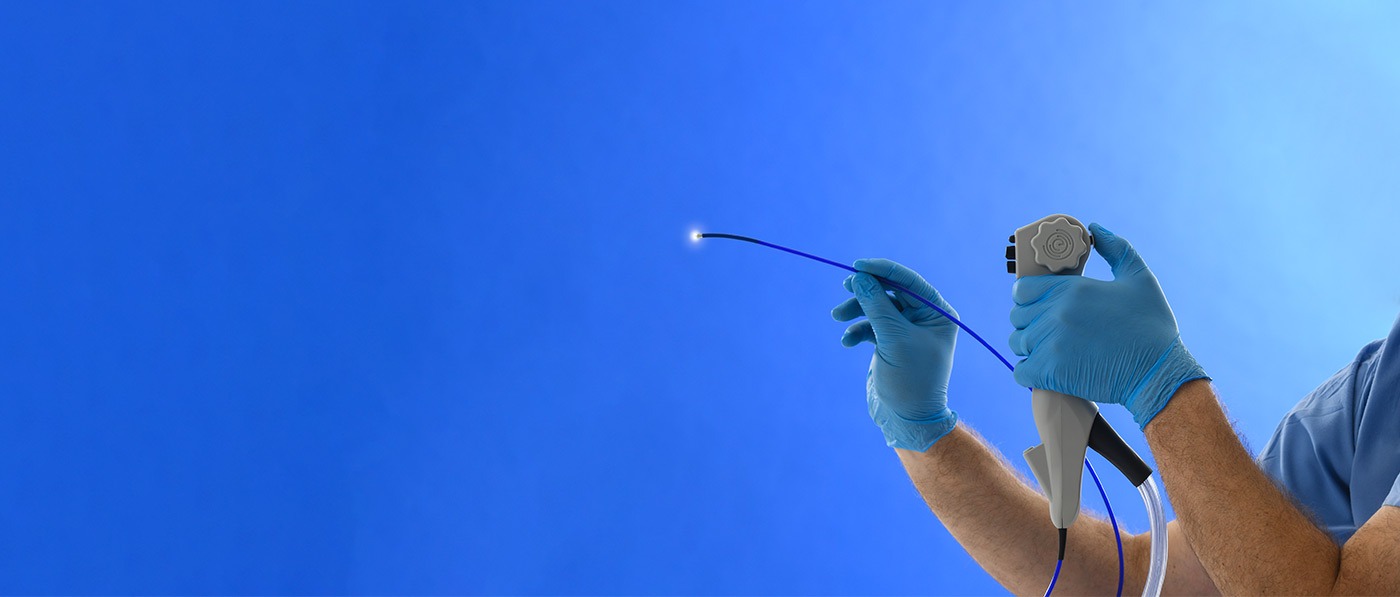

-1.jpg?width=4633&height=2606&name=GettyImages-492938248%20(2)-1.jpg)

.png?width=2500&height=1267&name=patents+pending+(3).png)

.png?width=1920&height=1280&name=blog%20image%20(1).png)